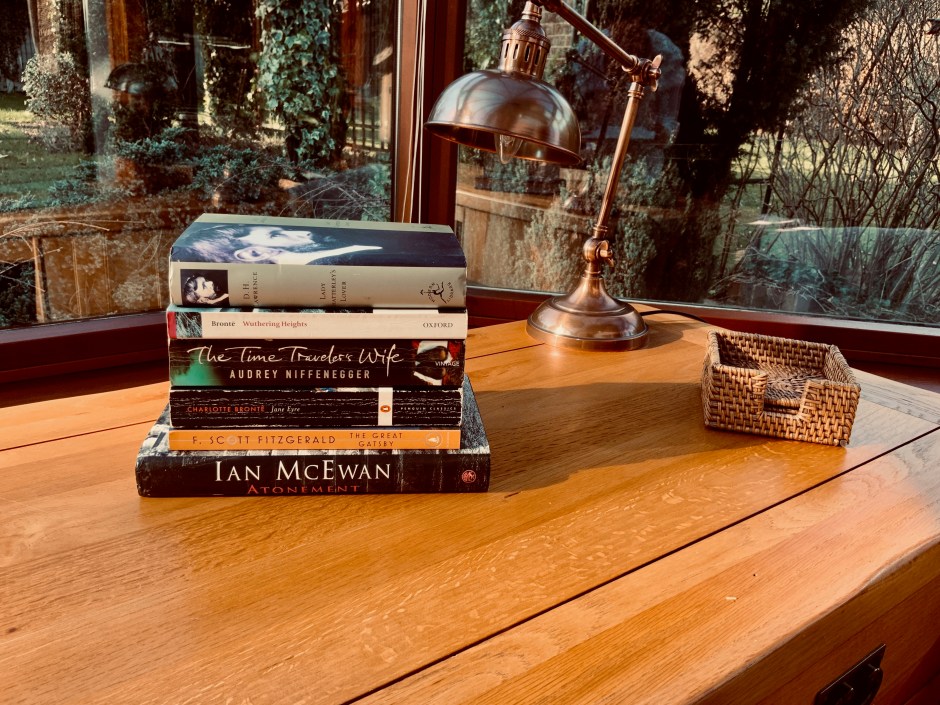

As I round up my all time favourite love stories for this blog post, I realise that not many are light-hearted romances. All are tinged with a sadness, a separation, a desperation or a secret: none are straightforward. Perhaps that’s why they have made such an impact on me over the years – the passion of desire is underpinned by extrinsic, circumstantial motivations, the highs of adoration are contrasted by the desperate lows of absence and the comfort of completely trusting and knowing another can be completely undone by a single, uncontrollable event. But there’s something in these intense emotions that run concurrent with love that is invigorating and addictive.

These love stories are more complex than the ‘boy meets girl, they fall in love, they overcome an obstacle and live happily ever after’ stereotype. Instead, nearly all of these endings do not see the principal couples together (in one way or another). In fact, it is only Jane Eyre that culminates in a happy, satisfied marriage. Most of the others, meanwhile, end on notions of hope, fulfilment or contentedness, with only one ending in tragedy. But it is this complexity of love, this opportunity for multiple, contrasting emotions that draws me in. As a fellow love-lover, Bolu Babalola explains in Love in Colour, “love and affection is magnificently multi-dimensional, both universal and deeply personal, its expression as nuanced, diverse and complicated as humanity itself” – love is intricate and convoluted, but it is fundamental and essential. What a juxtaposition.

So as we approach Valentine’s Day, these romances may not be for those who crave escapism, geniality, delight or cheerfulness. But they do make you feel, they tug at the heartstrings and delve into emotions that are currently close to reality in this age of social-distancing, and I find I strangely take comfort in that. So sit back, relax and enjoy this collection of ardently romantic and wistfully passionate love stories.

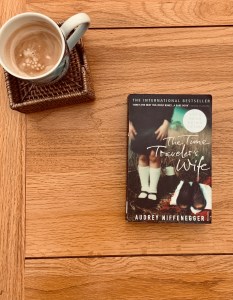

The Time Traveler’s Wife by Audrey Niffenegger (2003)

“Everything seems simple until you think about it. Why is love intensified by absence?”

Unpredictable time-travel, a fragmented chronology and the frustration of absence underpin this unconventional romance. The passion, desire, longing and comfort in love are painfully splintered in an examination of miscommunication and emotional distance in relationships. Despite these somewhat melancholy existential explorations, The Time Traveler’s Wife still indulges in the adoration, excitement and warmth of finding a soul-mate, rendering this novel a rollercoaster of emotions and a love story like no other.

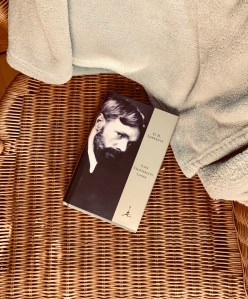

Lady Chatterley’s Lover by D. H. Lawrence (1928)

“All hopes from eternity and all gain from the past he would have given to have her there, to be wrapped warm with him in one blanket and sleep, only sleep. It seems to sleep with the woman in his arms was the only necessity”

Privately published in 1928 with a censored version appearing in the UK in 1960, the subject of an obscenity trial and previously banned in the US, Canada, Australia, India of Japan, Lady Chatterley’s Lover is a novel synonymous with scandal and indecency. It follows the story of a married, upper-class woman who longs for physical and emotional fulfilment, driving her to have an extra-marital relationship with the groundkeeper on her husband’s estate. It is the founding contributor to erotic literature, while the themes of class and emotional satisfaction carry the plot alongside the more intimately detailed love-scenes.

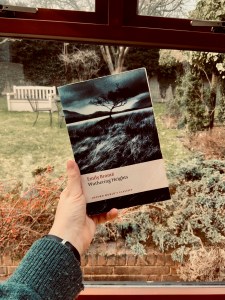

Wuthering Heights by Emily Bronte (1847)

“If all else perished, and he remained, I should still continue to be; and if all else remained, and he were annihilated, the universe would turn to a mighty stranger.”

Unruly moorland, ghostly hauntings, impassioned grave-digging and an unusual love-story that’s never realised on earth, Wuthering Heights tells the tale of Catherine and Heathcliff’s complicated and frustrating relationship through a framed narrative with the underlying themes of theology, religion, childhood and race.

Atonement by Ian McEwan (2001)

“Finally he spoke the three simple words that no amount of bad art or bad faith can every quite cheapen. She repeated them, with exactly the same slight emphasis on the second word, as though she were the one to say them first. He had no religious belief, but it was impossible not to think of an invisible presence or witness in the room, and that these words spoken aloud were like signatures on an unseen contract.”

Taking place over three time periods, Atonement is a metafiction novel where the romance feels short-lived. The one act of intimacy is sabotaged by a single lie, leaving the rest of the novel to deal with the fallout, emotionally and physically. Themes of perspective, guilt, class and injustice permeate the storyline while questions of authenticity and authorship are raised.

The Great Gatsby by F. Scott Fitzgerald (1925)

“His heart beat faster and faster as Daisy’s white face came up to his own. He knew that when he kissed this girl, and forever wed his unutterable visions to her perishable breath, his mind would never romp again like the mind of God. So he waited, listening for a moment longer to the tuning fork that had been struck upon a star. Then he kissed her. At his lips’ touch she blossomed for him like a flower and the incarnation was complete.”

Gatsby’s compulsion to reignite a relationship with his former beau, Daisy, drives the events of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s modern classic. Set against the backdrop of sultry Long Island summers, champagne-dazzling parties and the opulence of the Jazz Age, The Great Gatsby slowly reveals the decline of the American Dream alongside Gatsby and Daisy’s thwarted relationship.

Jane Eyre by Charlotte Brontë (1847)

“There was no harassing restraint, no repressing of glee and vivacity, with him; for with him I was at perfect ease, because I knew I suited him; all I said or did seemed either to console or revive him. Delightful consciousness! It brought to life and light my whole nature; in his presence I thoroughly lived, and he lived in mine.”

In this more traditional romance, the reader follows Jane’s life and obstacles as she tackles boarding school, becoming a governess, meeting Mr Rochester, discovering his secret, all culminating in the infamous line, “Reader, I married him”. Through this Bildungsroman, Charlotte Brontë successfully and subtly unwinds the intricacies of falling in love, the complex obstacles involved and the ultimate peace and contentment possible.

All pictures are my own unless otherwise credited. Permission must be obtained before any reproduction and credit must be issued in any reproduction