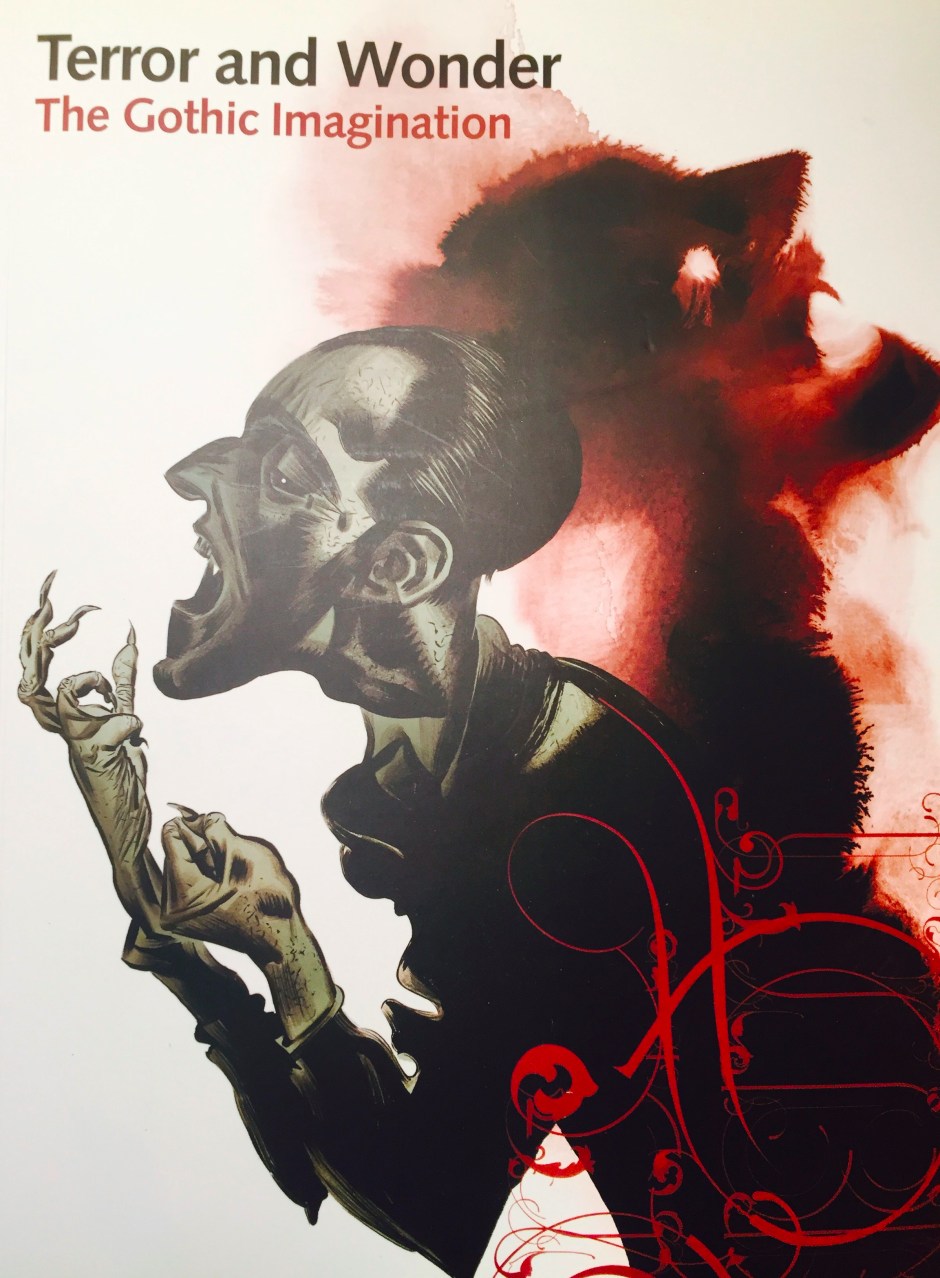

Terror and Wonder, The Gothic Imagination: British Library Exhibition

This winter, the British Library has held an exhibition on gothic culture, exploring the use of terror and wonder in literature, art and film through the centuries, starting in 1764 with the publication of The Castle of Otranto and ending with gothic culture in the modern day. In going through each era in chronological order, it was very clear how the word ‘Gothic’ is an umbrella term covering literature, film and art which has evolved and developed for over 200 years. Whilst Horace Walpole wrote The Castle of Otranto with the aim of merging both Realism and Romanticism – combining plausible situations with mystical and sublime events – he really founded a new genre and style of writing, using terror as a means to engage his readers, which permeated into art, music and film over time, right up until today. In giving this overview of the gothic genre, juxtaposed with the detailed descriptions of each individual gothic turning points, the exhibit allows visitors to walk through time and appreciate the minute progressions of the genre. It is in this way that modern society can begin to understand how the gothic genre commenced with The Castle of Otranto, evolving to having now produced The Twilight Series.

It has hard to imagine that: The Italian (Ann Radcliffe), Jane Eyre (Charlotte Bronte), Dracula (Bram Stoker), Bleak House (Charles Dickens), Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde (Robert Louis Stephenson) and The Shining (Stephen King), all belong to the same genre of literature. There are two main elements that connect these novels: the suspense caused by the style of writing and the use, or implied use, of the supernatural. The exhibit shows how these vast novels (in terms of plot and subject base) not only further the variety of the gothic genre, but also create a timeless impression: each novel, painting or film contributes to the genre and they are in communication with pieces of art which have preceded them. Despite this longevity within the genre, however, the exhibit explains how each of the novels mentioned were particularly suspenseful, frightening or terror-inducing due to that society’s fear at that time. For example, Bleak House’s representation of the poor in the crowded, dark, foggy and eerie back streets of London would have terrified the upper classes who were afraid of those lower in society and the mixing of social classes. The Italian and Castle of Otranto, however, relay stories of ancient churches in medieval times, creating a whole different level of suspense according to society’s fears.

Terror and Wonder, The Gothic Imagination primarily allowed me to understand the gothic genre as an ongoing, vast and diverse element of culture in our modern day and throughout history, but also the impact of certain eras on the pieces of art produced. The detail to certain eras and artifacts, and then the impact of this in the journey of the gothic genre as a whole was the most interesting and satisfying, as it allowed visitors the opportunity to have an overall view of the genre, as well as detailed stories and facts about each of the pieces of works, their situations and their artists. The opportunity to see first hand original manuscripts, sketches and notes of the authors and artists is an aspect of this exhibition that was the most momentous, as it connected me, in the modern day, to the author and their mindset at the time of writing – an indescribable feeling. This exhibition is open until Tuesday the 20th of January at the British Library, London.